What are mast cell tumours?

Mast cell tumours are one of the most common type of skin tumours in dogs. They arise from mast cells, which are a special type of cell which play a part in the animal’s immune system. They are primarily found in the skin and play a part in inflammatory reactions, releasing a chemical called histamine. Mast cell tumours can vary greatly in shape and appearance (which often makes diagnosis difficult) and they can be present on or under the skin (in the subcutaneous tissue). In rare cases, mast cell tumours can arise from areas other than the skin. Mast cell tumours can occur in all ages and breeds of dogs, but the average age at presentation is ~8-9 years of age. The exact cause of mast cell tumours is still uncertain. A viral source has been suggested, as well as hereditary and environmental factors. It is quite possible that there are a variety of different causes for the development of this tumour.

How do I know if a lump is a mast cell tumour?

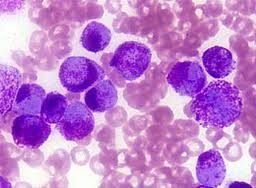

Examination of any skin lump which is of concern generally involves a fine needle aspirate (FNA). This involves inserting a small needle with an attached syringe into the lump and aspirating some cells. This can usually be done with the owner present in the consultation room and rarely requires sedation (unless the mass is in a very sensitive area or the dog is very wriggly or aggressive). The cells collected are then examined under the microscope for the presence of purple granules, which is the classical appearance of mast cells. We also carefully examine associated lymph nodes at this stage to determine whether they appear to be affected.

How can mast cell tumours be treated?

Depending on the size and location of the tumour, our treatment options vary. Mast cell tumours can have different ‘grades’ of severity and in order to adequately determine how ‘aggressive’ a tumour is, we need to perform histopathological analysis. This involves sending off tissue from the tumour to an external laboratory for analysis. This sample is most commonly obtained via surgical removal of the tumour, but when surgery is too difficult (either due to the location or size of the tumour), a biopsy of the tumour can be undertaken.

- Grade 1 tumour (well differentiated) – commonly benign and complete surgical removal of the tumour is usually curative.

- Grade 2 tumour (intermediately-differentiated)- adjunctive radiotherapy or chemotherapy may be required, depending on the surgical margins

- Grade 3 tumour (poorly differentiated) – behave in an aggressive manner and usually metastasise (spread to other parts of the body) early in the course of disease.

Adjunctive chemotherapy +/- radiation therapy is recommended. This is often combined with careful examination of lymph nodes, abdominal ultrasound and chest x-rays to look for any evidence of metastases.

Surgical removal

This involves a stay in hospital and a general anaesthetic. Because of the nature of mast cell tumours, a wide surgical margin around and deep to the tumour is taken to ensure that the entire tumour is removed; consequently the surgical wound is usually much larger than the tumour. If the associated lymph node appears to be involved, we may also remove this at the same time. If histopathological analysis reveals that the excision was incomplete (ie there are still tumour cells remaining in the tissue), further surgery or other adjunctive treatment (irradiation or chemotherapy) is often required.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is often used as an additional palliative treatment for dogs with a grade 3 mast cell tumour or in dogs where there is already evidence of metastatic spread. Chemotherapy can sometimes be used when surgical excision is difficult or impossible or where the functional or cosmetic effects of removal would be unacceptable. Chemotherapy is occasionally used to shrink a large tumour prior to surgery. A chemotherapy protocol would be tailored to each dog and generally 40-50% of dogs show some response to therapy. Chemotherapy in animals uses much lower drug doses than similar drugs in humans, and hence there are fewer side effects. The most common side effect is a suppression of white blood cell production and a decreased ability to fight infection. Regular blood testing is performed to ensure blood cell production is adequate before administering the chemotherapy agents. Vomiting and nausea are other possible side effects.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is used primarily for cases where removal is not possible (around the face or lower limbs) or when a tumour is inadequately excised. Acute and self limiting skin reactions can occur at the area irradiated, however these usually subside within 1-2 weeks of completing treatment. Radiation therapy is quite effective for controlling local tumour regrowth, but it does not treat metastases.

What is the prognosis?

Mast cell tumour grading (usually following surgery) provides the best predictor of prognosis. Dogs with a higher grade tumour, with lymph node involvement, or those that are systemically ill tend to have a worse prognosis. If a grade 1 tumour can be completely removed via surgical excision, this treatment is usually curative. While many mast cell tumours can be cured by appropriate management, dogs that get one mast cell tumour can often develop separate mast cell tumours elsewhere on their skin at other times in their life. It is therefore important to regularly check your dog for any new lumps and bring them to the attention of one of our vets as soon as they are noticed. As with all tumours, prompt recognition and treatment is very important in obtaining the best possible outcome.